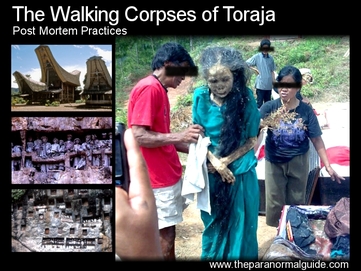

In August the corpses are taken from their resting places to be washed, groomed and dressed, before being walked through the village, back to their coffins.

A Interesting Tradition

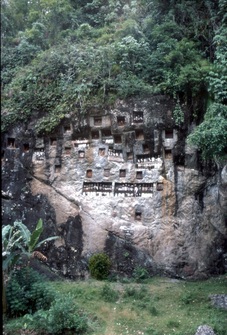

A Toraja cliff studded with 'burial' locations.

A Toraja cliff studded with 'burial' locations. Once a year in August, the ritual of Ma'Nene takes place. During this period many families (in this case villages, where each village makes up a family unit) climb the cliffs and enter the caves of the nearby countryside, in order to collect the corpse of their dead relatives, to bathe, groom and redress.

The mummified corpse is then paraded through the village, standing upright, and taken back to its place of rest.

Interesting, if not a little macabre maybe, but this process only echoes a older ritual that took place before the Toraja lost their isolation to Dutch colonisation.

The 'Walking' Corpses

One of the 'Walking Corpses'.

One of the 'Walking Corpses'. The reason for this caution was because the Toraja believed that when they died the spirit would linger around the body before it could be guided to 'Puya', the land of souls.

In order for this to take place, the body needed to be with the family for the process to occur. If a person was far outside of the territory when they died, they may not be found and their spirit would forever linger with the body.

Luckily the Toraja had a means to deal with lost bodies, though it was expensive and not open to everybody.

The services of an 'expert' (I believe the name for their practitioners of 'magic' is lost) who could call out to the lost body and soul, and make it walk back to the village. The corpse, having heard the call, would then rise and begin its stiff, expressionless walk back to its home.

Once a walking corpse was located, people would run ahead to warn other people that it was heading in their direction. This was not out of fear, but rather another aspect of the ritual, to ensure it would make its way home as soon as possible. If anyone made direct communication with the corpse, it would collapse to the ground, once again lifeless. The runners would tell all those in its path that this was indeed a walking corpse, and not to make contact.

Traditional Toraja homes.

Traditional Toraja homes. The feast could be quite expensive, and the higher up in class the family, the more expensive the feast. The feast would be attended by thousands of the Toraja, and could last for days, and include cock-fights, the slaughter of buffalo (the more buffalo the richer the family) and chickens.

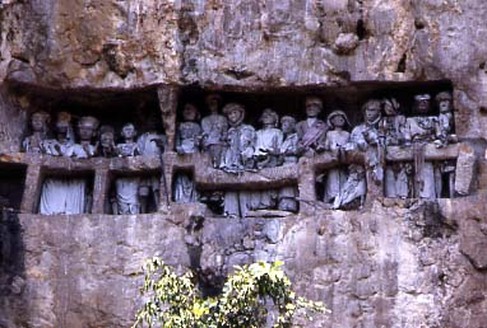

Cliff 'burials'.

Cliff 'burials'. The Toraja firmly believe that the body and spirit should be placed between the heavens and earth, hence the burial at height. Wooden effigies are carved of the dead, and these can be seen decorating the cliffs and the mouth of caves.

From here once a year the bodies go through the process of washing, grooming and dressing to once again walk through the villages. These days the bodies are supported and walked.

However, according to some observers, not all the magic of the ceremony has left the Toraja. Sometimes, and if the deceased is quite prominent, the magic is still used and the corpse can be seen breathing before its initial burial, and the decapitated bodies of the buffalo, slaughtered in offerings, have been brought back to life to parade headless about the ceremonies.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed